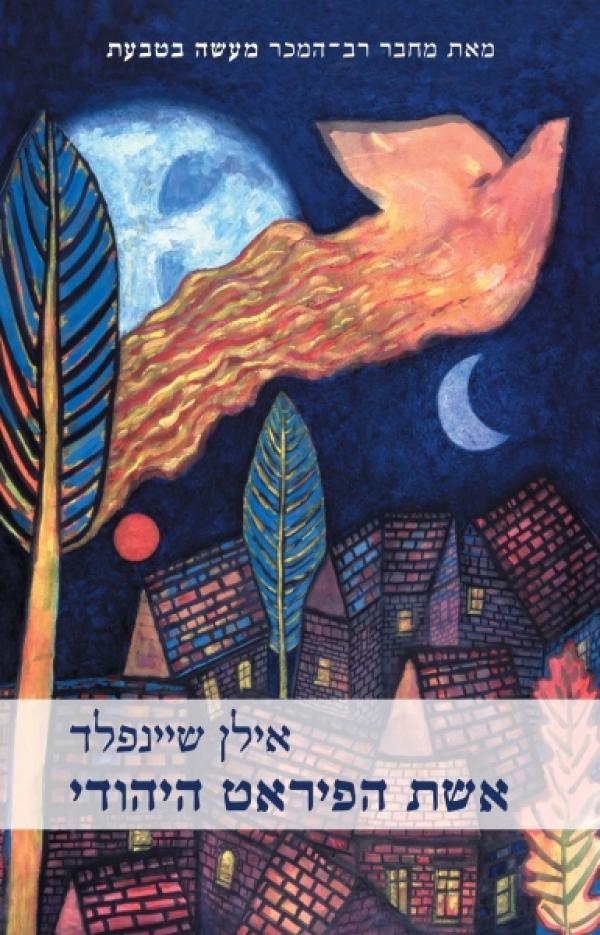

Ilan Sheinfeld’s first companion, Sa’ar, died of Hypocalemic Periodical Paralysis in Amsterdam in 1986. Sheinfeld gently – and bitterly – explains that he was not present when Sa’ar died, because shortly before his death, Sa’ar left Sheinfeld for a woman – poet Sheli Elkayam. Everything in Ilan Sheinfeld’s life changed following Sa’ar’s death. During the first four years of intense mourning, Sheinfeld – who is primarily a poet, kept daily autobiographical notes in an attempt to define for himself the “widowhood of one man for another man.” Sheinfeld’s first novel, “Shedletz,” grew out of these notes. It is being published this week by Shufra Press – a publishing house for homosexual literature founded by Sheinfeld himself.

“Shedletz,” which includes Hassidic tales and miraculous stories of folklore and mysticism, describes a world that existed three or four hundred years ago. The central character is a Jew named Yossel Green who goes through two incarnations in his life – the first as a frog living in a pond, the second as the gravedigger of the Polish town of Shedletz. After the town in destroyed, Green moves to Israel, settles in Tel Aviv, secretly writes his memoirs, and makes a living as a publisher.

Sheinfeld, whose parents are Holocaust survivors, says that before he began writing, he realized, “how much I didn’t know about their lives and how much I had to learn in order to relate to them properly. My parents never spoke about the Holocaust or their childhood in Europe.”

Two years of writing went by before Sheinfeld discovered his own inner frog: “I wrote continuously. I couldn’t stop. I started by writing stories about the various characters in the town, and later the main character of the Jewish frog came to me. I’d started therapy in 1992 and had just begun to touch upon who and what I am. It was a decisive and stunning experience, but also a very painful one. It utterly controlled me. It was a metamorphosis.

“Later, I understood that for 30 years I had suppressed – in the area that Jung calls ‘man’s shadow,’ everything that people couldn’t accept about my behavior. It grew and grew into a Jewish frog that lives in a pond in a large Jewish town in Poland. The pond is the internal darkness within me, which is so rich in creative impulses and all kinds of things I couldn’t live with as Ilan Sheinfeld – the Zionist youth counselor, poet and editor, graduate of the Tel Aviv University literature department and little homo.”

Mourning wasn’t the sole impetus behind Sheinfeld’s decision to turn to prose writing. It started when he was assistant literary editor at the now defunct daily Al Hamishmar. Each holiday issue would include holiday-related stories and poems, as well as an interview with a literary personality.

“I said to Yael Lotan, ‘Are we going to interview the same old people again? Let’s make up an interview with a writer who doesn’t exist.’ At the time, I’d been reading a lot about Eastern philosophy and mysticism, so I suggested an interview with an Indian writer named Indad Chatarjee. According to the biography I invented for him, he was a writer and intellectual born in 1929, educated in Cambridge, who moved in 1974 to Switzerland, where he lived with his Jewish wife, Idit Zinger. I added that Chatarjee had published several books and essays, that he rarely gave interviews, and that he was in Israel doing research for a book about the Templars.”

Sheinfeld went home, sat down in front of his typewriter and typed out a long interview with Chatarjee, ranging from such topics as his earlier work, the State of Israel, religion in general and Judaism in particular, the Holocaust, the writer’s exile and even Israel’s nuclear policy (at the time, Sheinfeld was a member of the Committee for Mordechai Vanunu). Just before the interview was scheduled to go to press, Lotan and Sheinfeld showed the interview to editor Mark Geffen. His reaction: “What a brilliant writer! Where did you find him?” When Geffen found out that the interview was fabricated, he burst out laughing and agreed to publish it.

“The editorial board was swamped with enthusiastic calls and letters,” Sheinfeld recalls. “One of the callers was Haim Pesah, then the editor of “Moznayim.” He was curious as to who this amazing man was and asked to read one of his books. I replied that I just happened to be translating a story of his, and I promised to send it to him as soon as I had finished. I had no choice – I went home and wrote the story “Lord of the Black Village.” I sent it to Haim and asked to meet with him should he decide to publish it.

“It was only when we got together that I confessed. Since I was already known as a poet, I asked him to leave the writer’s name on it and add that I was responsible for the Hebrew translation. It’s tremendously pleasurable to write “with a mask on.” I’d grown up with a certain idea of myself – that there were certain things I couldn’t do. For the first time, I broke through those boundaries. For the first time in my life, I let myself do what I wasn’t permitted to do before.”

Sheinfeld came to see the inner shadow he had read about in Jung’s writings as a demon (“shed”). When he added the word “letz” (“jester”) to it, he came up with the name “Shedletz.”

“I was convinced that this was an incredible combination and that I’d come up with an original name for a novel. In 1992, I published a chapter from the book in a literary magazine. It was the day before a holiday, and when I arrived at my parents’ home in Ramat Hasharon and my mother said, ‘We read your story. What made you think of writing about the town where I was born?’ I was stunned. She laughed and said, ‘I was born in the town of Shedletz, 40 kilometers from Warsaw. You must have heard the name around the house and thought that you’d made it up.’

“There was no point in arguing. I just asked her to tell me about the town, since I’d written all kinds of things, and I wanted to corroborate them – for example, a lot of stories about demons and jesters leaping from the trees into the river. ‘Of course,’ she said. ‘Your grandmother used to tell stories about phantoms jumping from trees.’

“It was overwhelming. I felt I had to write this book in order to create a past for myself. The subtitle of the book is ‘Memories’ – these are memories of dead Jews who sat on the desk and dictated their memories to me. That’s why my mother’s reaction was odd. She had told me so little about her childhood.

One of the characters in the unusual Jewish town in Sheinfeld’s book is Shlomo Yitzhak, the son of a Jewish witch and a priest, born with a cross stamped on his chest. The letters of God’s name are revealed by rubbing on the cross. When Shlomo Yitzhak’s mother dies, he starts wearing her clothes. Before long, he grows breasts and goes to live with Vasily the Gentile, who was blinded by a stone that bounced back and hit him when he tried to throw it at Shlomo. Later on, Shlomo becomes a kind of holy man with supernatural powers.

“There’s a particular phenomenon wherein the shaman of a tribe is a homosexual or an androgynous being,” Sheinfeld explains. “Of course, this couldn’t be the case in a Jewish town. Essentially, what I did was to put things related to my own life into this imaginary town. I attempted to create a past for myself that I could connect to.”

In the book, Ilan Sheinfeld’s alter-ego is called Izzy Green, a young fair-haired man. Izzy’s parents are determined to prevent him from learning about their past in the Holocaust. On Saturdays, he goes with his father to the synagogue, and Izzy (like Sheinfeld) is sucked into “the black hole that lay lurking beneath the three prohibitions that constantly fluttered about him during his childhood – no talking about the Holocaust, sex or death… They all abandoned him… God, his grandmother, his father and mother, his childhood playmates, but, more than anything, he abandoned himself – all the while withdrawing into the pond of his childhood memories.

“This was the abyss into which he propelled himself even after belatedly responding to the shy overtures of one of his male classmates, indulging in several weeks of hesitant, virgin lovemaking in the dust of a construction site. It is also the pond in which, stripped of all sanctions for his existence, Izzy Green began to search for what he had earlier discarded – another man’s image.”

Sheinfeld, 38, is the eldest of four sons and comes from a family with a traditional religious background. His mother Sara was a young girl when World War II broke out, and went with her parents to the Warsaw Ghetto. From there, the family escaped into the forest. Sheinfeld’s Serbian-born father, Avraham, and his father’s brother were forced into a death march in Romania, but the two managed to survive. Sheinfeld’s parents’ families wandered through Europe during the war and came to Israel separately in 1949. Sara and her family settled in Bnei Brak; they were affiliated with Hapoel Hamizrachi. She graduated from an all-girls school and trained as a laboratory technician. For a while, Sheinfeld’s father and his family moved back and forth between the Migdal and Ramle transit camps, before settling in Tel Aviv. His father studied law and social work at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Today he is a judge and vice president of the juvenile courts. Sheinfeld knows few details about his parents’ romance. “I’m not sure I could distinguish the true story from what I’ve imagined about it,” he says.

After they got married, his parents went to live in Neve Magen. Later, they moved into his grandparents’ house in Ramat Hasharon’s Pecker neighborhood. “The Pecker neighborhood was built by survivors from my father’s town. The synagogue is in the center and is surrounded by houses and alleyways – that’s the model for Shedletz. My father was on the board of the neighborhood and the synagogue. The Cohen who circumcised my father and conducted his bar mitzvah did the same things for me. Everything in that neighborhood was Yiddishkeit. There’s a big panel in the synagogue with the names of all those who have passed away.”

His mother brought many books of Judaica with her from her parents’ home. When Sheinfeld was young, his father would take him to the neighborhood synagogue to show him the liturgical texts. “He taught me to pray in the same way you read a poem – this had a big influence on my own poetry.”

The four Sheinfeld sons received a secular education. Sheinfeld went to the Golan elementary school and Rotenberg high school. On Saturdays, he would accompany his father to the synagogue. He learned Yiddish from his grandmother. When he began to develop as a poet, his father took him outside for a man-to-man talk, delicately suggesting to him that he become a literary researcher or literature teacher. He warned him that a poet’s life can be difficult and that poets have a tendency to see the world in stark black and white terms.

After two or three years, the father saw that his advice had not been taken, “and then he did the most beautiful thing. He bought me a typewriter and said: ‘So you’ve decided to become a writer? Then you should have your own typewriter.’ When I was discharged from the army, he financed the publishing of my first book, ‘Enchanted Lizard.’ He said: ‘Take some money and publish your poetic identity card.'”

At school, Sheinfeld was taunted by the other children. “My ears stuck out, so they called me ‘donkey ears.’ When we moved from Neve Magen to Ramat Hasharon, the kids called me ‘rabbit.’ As a child, I was very loved in my family, but I was always different – softer and more sensitive, and less athletic. I read a lot and was preoccupied with my own internal world.”

The harassment at school came to an end when Sheinfeld was in eighth grade and was put in charge of decorating the classroom. He says that the activity and the chance to contribute socially saved his life. A year later, he became a youth movement counselor. “Up until the middle of my military service, I was a counselor for all age groups and levels. I was a group coordinator in charge of all the other counselors. What’s interesting is that, at the same time, I was growing as a homosexual, as a poet and as a little Jew.”

Sheinfeld’s parents did not talk much about sex – “perhaps because of their religious background, or perhaps because I was their first child, and they were not yet experienced in doing so.” When his parents learned that he was homosexual, they were horrified and reacted angrily. He was then 17 and also liked girls very much. His parents’ reaction caused him to retreat for some time from declaring his sexual identity. He went out with girls again and struggled with this issue until he was 21 or 22. When he finally was prepared to come out, his parents accepted it as well.

Sheinfeld declares that the taboo surrounding homosexuality is a Jewish taboo. “The word that scared me the most was “karet” (divine punishment by premature death), which is the most severe punishment Judaism has for people like me. How could I have done such a thing to my parents? I didn’t do this to them. It simply happened. I pitied them when I understood what it was doing to them. Perhaps that’s why it took me so many years to come out of the closet. I think they’ve forgiven me, and I’m sure they’re comforted by the grandchildren they have from my brothers.”

There was no stopping Sheinfeld from the moment he became comfortable with his sexual identity. For many, the name Ilan Sheinfeld is more closely connected to homosexuality than to poetry or literature. Eleven years ago – a year after Sa’ar’s death, Sheinfeld published a book of poetry containing love poems that describe male love in extremely bold language.

When the book came out, Sheinfeld gave an interview to Ha’aretz Magazine in which he described his journey of discovery toward his homosexual identity. His first experience with another boy was in the eighth grade, when he was a youth counselor. At 16, he was doing his national service on a kibbutz when he slept with an older man for the first time. He continued to go out with girls, but also had an affair with a male gym teacher. During his army service and his studies at the university, he had some non-committal relationships with men whom he met at homosexual meeting places.

Sa’ar was his first great love, and they lived happily together until Sa’ar left with Elkayam for Amsterdam. After Sa’ar’s death, Sheinfeld went to live with Elkayam. “We lived together for a few months, and each day I imagined that Sa’ar would return home. Sheli is a special kind of person. I needed her then.” When Sa’ar died, Sheinfeld gave up the idea of an academic career. He had nearly completed his master’s degree in literature when he left the university and started to work in journalism. He continued to mourn Sa’ar until 1992, when he met his current companion Adi Ness.

“Shedletz” has made him feel like new, he says. “This book contains a lot of Eros, lust and violence. It cleansed me of feelings I had hidden inside. This invented past made me complete as a person. I suddenly felt that I had a foothold in life – the fact that I had made it up was of no consequence. It’s there, and now I can travel to Poland. I’ll be very glad if the book leads people to think about the black hole that we are all in. Another important point – I opened the office in 1995 after I finished writing.”

He doesn’t see any conflict between his being a poet and working in public relations. “My parents taught us that we had to work to support ourselves – that we should never live off of somebody else.” Sheinfeld says that two months ago, none other than Uri Lifschitz approached him to do some public relations work. The same Lifschitz later used some extremely harsh words to condemn homosexuals. Sheinfeld says that Lifshitz’s homophobia – and that of singer Meir Ariel – is dangerous, because it could lead to real acts of violence against homosexuals. “When people like Lifschitz and Ariel open their mouths, it can influence people; they have public impact.’ Sheinfeld says that, for him, public relations is “intellectual work, as strange as that sounds.” It’s also practical: “At least, I make a living. No one supports me. I purchased my apartment with key money; I lease my car, and I still want to have at least one child and travel abroad once a year. I’m 38, and I can’t be a poverty-stricken poet.”

Sheinfeld’s partner of the past six years – painter and television researcher Adi Ness – shares his desire to have a child. But it’s not yet feasible. “I want to leave this world knowing that I gave everything I have within me to create another living being, and that he will do something with this – that he will go on and develop. I just want to see it with my own eyes. We’re searching for the right woman for the assignment. The truth is that I’ve sometimes amused myself with the idea of mixing Adi’s and my sperm together to see what happens.”

Ha’aretz, Friday, January 8, 1999

You must be logged in to post a comment.